Marcello Cantoni unravels the controversy surrounding San Giovanni Rotondo

Pictures by Andrea Poidomani

Where is the line between religion and business drawn? Between spirituality and the apparently cynical and insatiable economy which revolves around it? This question has many answers and is difficult to explain in a few words, but it’s an argument which both fascinates and divides people.

In San Giovanni Rotondo, a southern Italian town with a population of 36,000, the question is of major concern. It was here, at the beginning of the last century, that a Capuchin friar settled and began his spiritual and worldly vocation. The friar’s name was Padre Pio but now, almost 50 years after his death, it has been changed to San Pio da Pietrelcina, after the Church decided to officially recognise the miracles that the friar seems to have performed during his life.

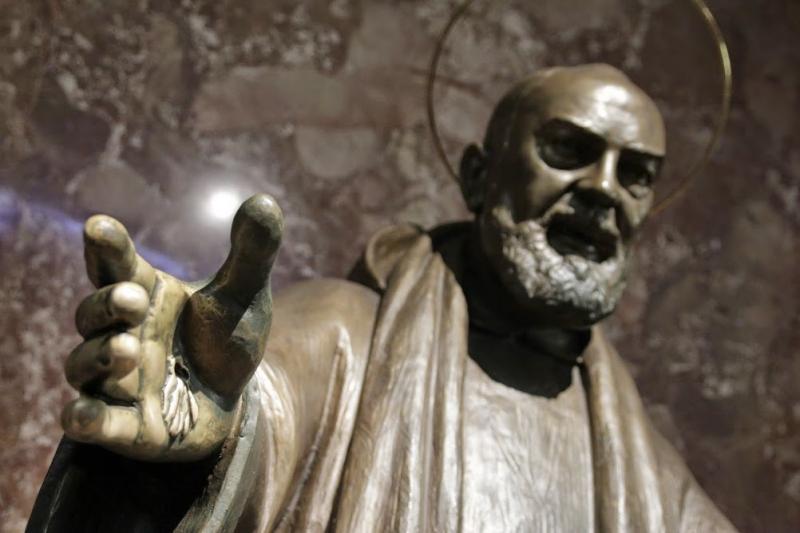

There is no doubt that he was a special man, able to attract millions of the faithful to himself. They came to San Giovanni in order to meet him and still today fill the town’s hotels and go to pray before his statue and be inspired by his energy, in the church which was built at his behest.

Patience Rewarded

I get there late in the afternoon, the evening falls on the town and the square begins to fill up with young people, scooters and sports cars. The Sanctuary is deserted, the pilgrims are resting in their hotels. To the side of the church is a small door, in front of which are some iron benches, which become occupied as the evening draws on. At four o’clock there are already four people there: two elderly women and a couple of young people with cameras and notebooks. As the hours pass, more and more people gather there and at nine in the morning, when the door opens, the queue seems endless. The people are waiting to speak to a friar who was a friend of Padre Pio and who seems to know how to console the human sprit and give advice. After five hours waiting with rosaries and coffee, with the hum of different languages, everyone with different hopes, the door opens and the faithful enter one by one.

A Golden Spirit

Particularly impressive is the new church, designed by Renzo Piano and inaugurated in July 2004, that can hold up to 7000 people" la sposterei così: "In 2010 the body of Padre Pio was moved from the crypt in the small Santa Maria delle Grazie sanctuary to a crypt housed inside a new church designed by Renzo Piano and inaugurated in July 2004 that can hold up to 7000 people. The crypt is covered with gold mosaics designed by Jesuit Father Marko Rupnik, using mostly the gold derived by the many ex-votos left by devotees from all over the world. This decision sparked a controversy and touched a nerve with many people who were already feeling very uneasy about the difficult balance between religion and business in San Giovanni Rotondo. Many among the Saint's followers found the grandeur of the new sanctuary and, in particular, the new golden crypt unacceptable, because in contrast with the way Padre Pio lived his life.

Even the view from the forecourt of the church is magnificent and unexpectedly revealing at the same time: the sacred and the profane seem to have arranged to meet each other once more. Just a few metres from the church with its towering cross, hotels and restaurants welcome the pilgrims, who arrive at San Giovanni in ever increasing numbers. They walk and pray all day long, but even they get tired and hungry. That is why the many hotels open their doors and the waiters in the restaurants lay the tables. The pilgrims only stay for a few days in San Giovanni and when they leave, they often feel a longing for ‘their’ Saint to be close to them. That is why the stalls and shops display their souvenirs, before which the pilgrims can pray when they get home.

The Padre Pio Industry

Religious zeal and controversy seem to go hand in hand in San Giovanni Rotondo. It is a conflict which will not go away easily, a dichotomy which is clear for all to see. The avenue which climbs from the town centre towards the Sanctuary is lined with hotels, one after the other. Within the sanctuary you find all sort of sacred art, images of Padre Pio, statuettes and photographs, as well as special boxes 'encouraging' you to leave a donation, 'offerte'.

There is also a line of stalls outside the hospital. Here they sell more questionable items like umbrellas, lighters and scarves, all bearing the image of Padre Pio, who at times seems to be turning up his nose at the company he is forced to keep. In fact, cheek by jowl with the images of the good friar there are all sorts of incongruous goods, from snowballs to toys. The stall-owners are rather wary, but after being complimented on the layout of their wares they relent and allow themselves to be photographed. However, they won’t comment on how business is, merely saying ‘If God wills it, it will go well.’

Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza

The search for answers continues inside the town hospital. The Casa Sollievo della Sofferenza (House for the Relief of Suffering ) was opened in 1956 at the behest of Padre Pio, who personally handled the offerings of the faithful to ensure that all the money would be used to construct the building. It was this which prompted the first signs of discord between the friar and the Vatican. Today, the hospital is a thoroughly modern institution, providing employment for many locals and able to treat 57 000 patients and 1.3 million out-patients.

It seems that, in this case, Padre Pio’s wishes have been respected, since the hospital, is now part of the national health system and is available to everyone. Anyone can be admitted, provided there is a bed free.

The Problem Resolved?

So, where is the line drawn between intimate spirituality and the business which revolves around it? I ask people who knew Padre Pio, interview several others and, of the many points of view, one in particular leaves an impression on me: a doctor from the hospital who, in answer to my questions, recalled the following: ‘Some years ago, in the church with the statue of Padre Pio, I saw something I will never forget. A woman was pushing her tiny, paralysed, child in a pushchair and, when she reached the statue, she took some of her son’s clothes from a plastic bag, placed them on the figure of the friar, then knelt and started to pray.’ At this point in the story, the doctor became very moved and it was a few moments before he could continue. ‘As long as that sort of thing happens, no controversy can sully Padre Pio’s image. These things are important, the rest is merely talk.’

I liked what he said. They were clearly the words of a man of faith, so he was perhaps biased, but it was a good answer to my question.