One fateful day 20 years ago, I stopped off by chance in a small, faded Italian spa town — and suddenly felt that of all the places in the world, this was the one where I wanted to live. I bought an appartamentino and have loved every minute since.

Now, though, it’s time to take stock. Climbing the stairs has become hard work. A second-floor apartment with a wonderful view is no longer quite the asset it once was, at least not here in the remote reaches of the Euganean Hills. But my partner and I have so many memories locked into the place that selling up is painful.

Happy memories are important, but I knew a tangible memento of our time here would be even better. That’s how I hit on the idea of commissioning a painting of my favorite view.

Joining a long tradition of patronage

This was hardly an original thought. Italian landscapes have featured in works by artists from Titian to Poussin. And creative people have a long history of being summoned to produce masterpieces at their patrons’ whims, particularly from the Renaissance onward. (Giangiorgio Trissino, one of Palladio’s early patrons, even insisted that the architect change his name in order to gain financial support. He was previously called Signor Gondola!).

No, I wasn’t placing myself in the august category of wealthy patrons, or imposing demands that extreme on anyone. But I liked to think I was taking part in a long tradition.

I first met Julian Vilarrubi on a painting course in Tuscany many years ago. He was, at that point, the typical struggling artist, brimming with talent but lacking in following (and funds). We reconnected last summer in London when he sent me an invitation to a private viewing at a new gallery in Hampstead — clearly having come up in the world. When he showed me a commissioned oil painting now hanging in a Los Angeles home, it convinced me to go ahead.

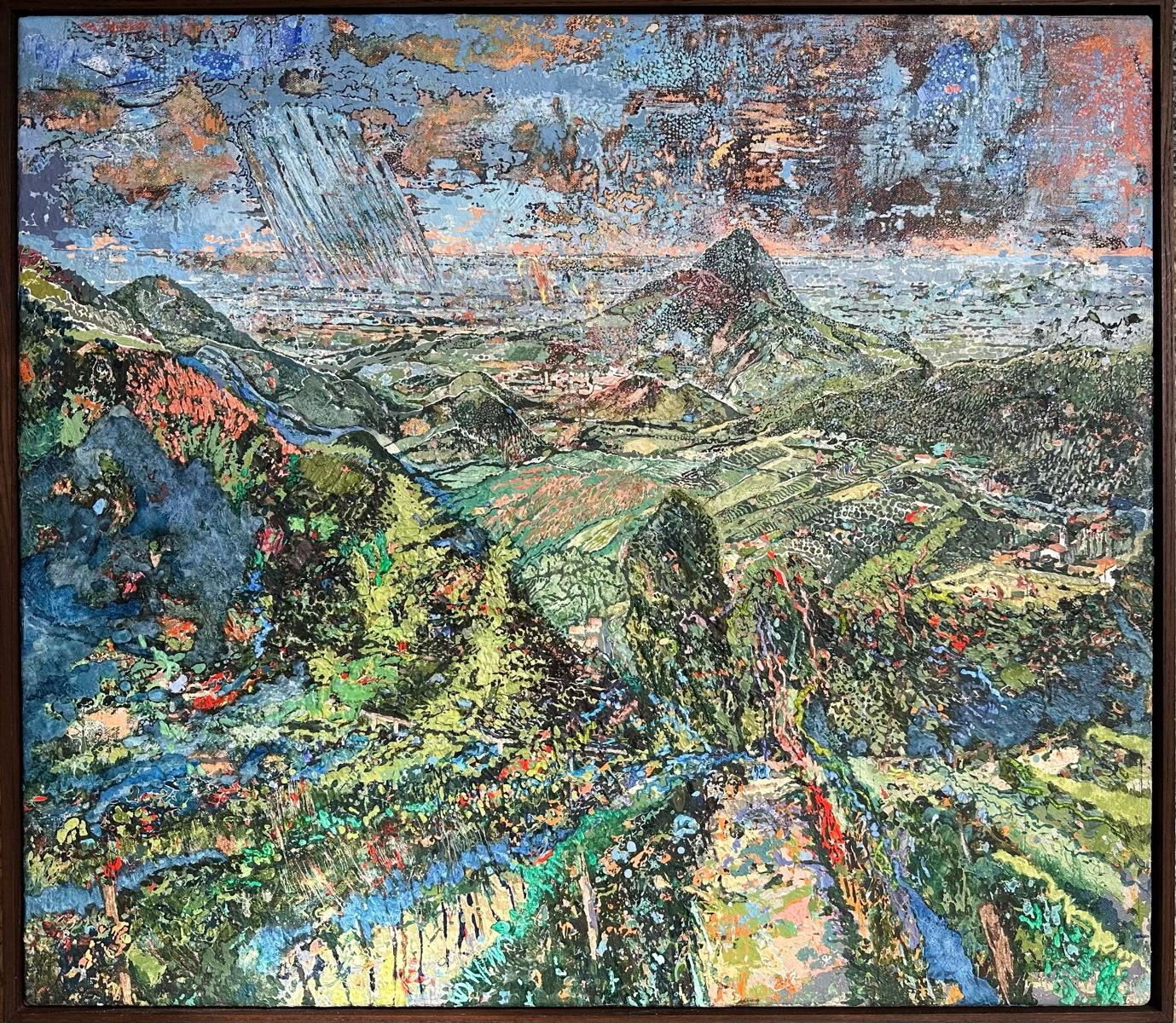

My painting would not be the landscape typically thought of as “Italian,” which draws too much from Tuscany’s rolling hills and avenues of cypress trees leading to ochre-colored farms and barns. In my area — glorious Petrarch country — volcanic hills with vineyards on south-facing slopes and chestnut trees facing north cluster around deep green valleys interspersed with small villages, each with its own bell tower. It’s an area of rare wild flowers and butterflies where time stands still, and that’s the sense I hoped Julian could capture.

In that pursuit, I invited Julian to stay in my apartment, and we set off one morning to look at my two shortlisted views. The first was along a strada bianca (unsurfaced road) to a bar called Da Teresa with a terrace overlooking a sweeping vista of vineyards, woodland and farms, with conical hills in the background. I’d planned for us to discuss the niceties over an aperitivo on the bar’s terrace, but we found it closed because all hands were needed for the vendemmia — a pity, yet an apt introduction to the area for the artist. We walked along discussing the finer points: Should the painting include the vines in the foreground where the grape pickers were hard at work, or begin at the low line of trees where the land falls steeply away? Bright crates and a red tractor featured in the foreground: Should they be included as points of color, or edited out? These were simple enough to answer.

But then the more difficult, reflective questions began:

“What’s special about this view?”

“Which season is important to you for the landscape and colors?”

“Do you prefer people to be present, or just the view of the countryside?”

“Should the view be literal, or could it be edited, retaining only the most important features?”

With tentative answers in my head, we drove off to the second viewpoint, along the ridge of Monte Fasolo. This was more complicated, as the view changes at every turn of the winding path, bordered by almond trees. Looking west, two hills hold between them Valle San Giorgio, with its tall gothic-style belltower. Another perspective reveals an interesting geometric pattern of sandy tracks across patches of green open fields, and patches of neat silvery-grey olive trees in dotted rows. The partially concealed face of a long abandoned quarry emerges after further walking.

More discussion. More searching questions. More memories.

The artist at work

The next day I offered to accompany Julian for the first tentative sketches. But his “no” was firm.

“Painting is a solitary activity,” Julian explained. He left for the hills alone at dawn the next morning, after citing the need to see the landscape in better light. (I understood, given my own countless hours alone at the desk, combing through my experiences in these hills and distilling them into a book.)

“When the sun is overhead, or when it’s hazy, [the landscape] all appears very flat,” he told me. “But when the sun is low in the sky, all the undulations and indentations become apparent, giving the landscape more depth.”

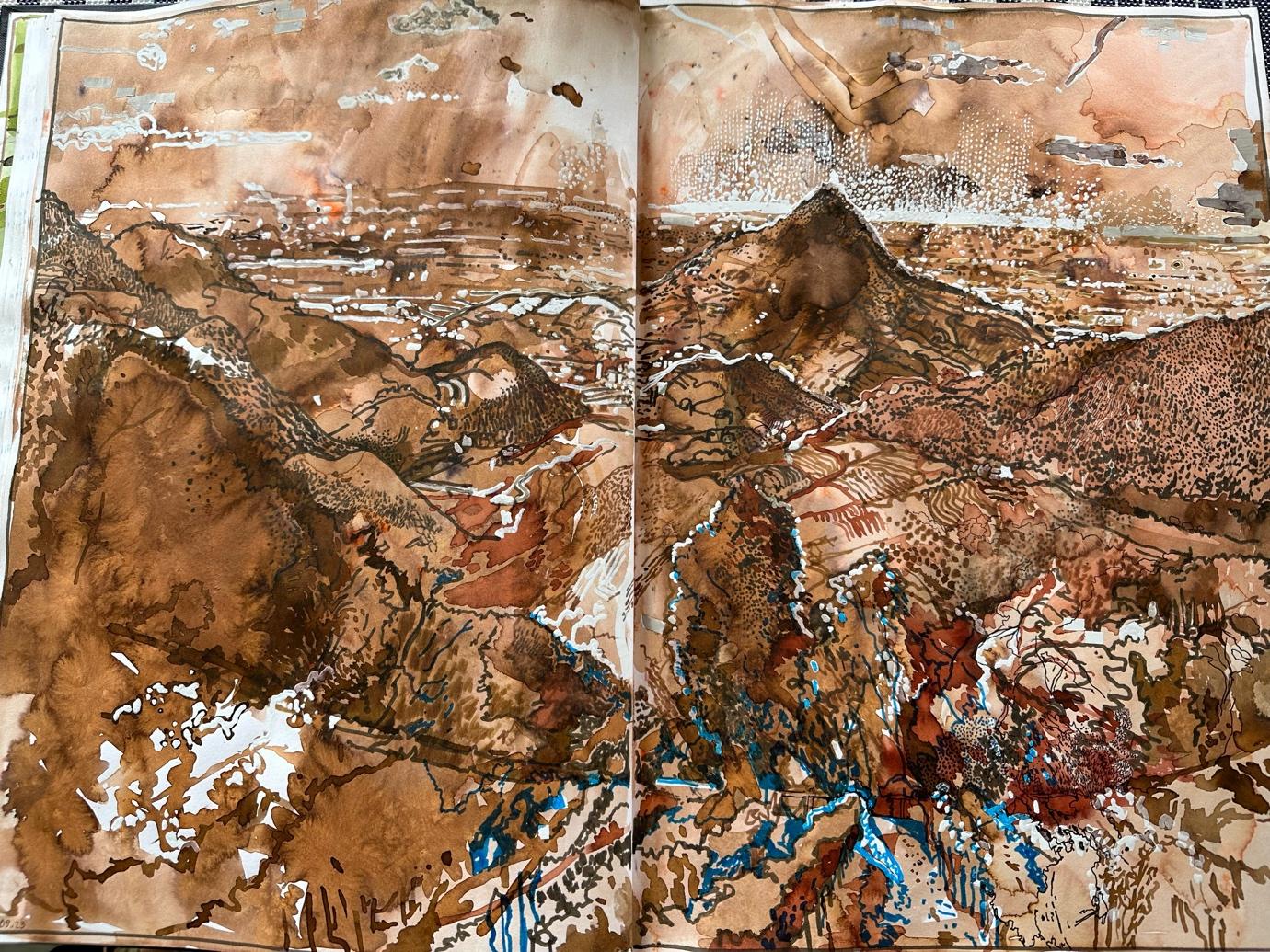

I spent the day imagining how things were progressing. On return, he handed over his large sketchbook, which I opened with nervous anticipation. My first impression was shock: There were all the recognizable features, but painted in sepia watercolor — nothing at all like the vibrant shades we’d seen together.

“This is how I record my initial impressions,” Julian reassured me. “It’s an absorbing experience. I need to find the tones and contrasts, best done in monochrome. Eventually, back in my studio, it will all be redone on canvas with the full range of oils.”

Another solitary day in the hills followed as he continued the work. We both agreed that the first chosen view with a clearer sky was the one.

Of course his sepia study is excellent — so good, in fact, that my partner has bought that as well. The final painting, delivered a couple of months later, is even better. In addition to being a treasured souvenir of all my years in the Veneto, it’s given me illuminating insight into the working practices of a professional artist — and, yes, a little taste of what the great Italian patrons were able to witness, too.

Where to find the view

From the Padova-Bologna autostrada, take the Terme Euganee exit and follow directions to Galzignano Terme. Turn left at the roundabout and climb steeply to the very top where there is a cross roads. Turn left and after about a mile, you reach the bar Da Teresa, where you can gaze out on the landscape from the terrace, cappuccino or Spritz in hand.