Italian Mosaics

ITA:

Use player to listen to Italian version

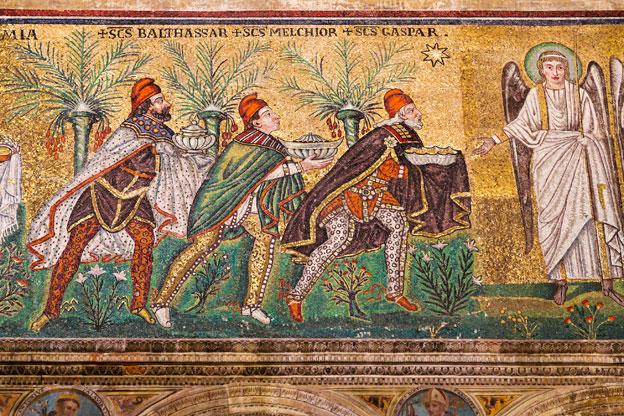

The fashion for mosaics grew in Italy from the early 2nd century when a simple black and white style emerged to meet Roman taste and fashion.

Mosaics were a status symbol, indicating both wealth and good taste, however they were also used to embellish public buildings like public baths (thermae) and shops. Two-colour mosaics were considerably cheaper to make, as they required much simpler techniques.

Dolphins, marine life, and sea mythology were popular images. Scenes depicting Roman life were also popular such as athletic games, hunting and circus spectacles. The images were lively and striking and more life-like than that of painting. Mosaics decorated walls and floors, and nymphaea (shrines to the gods) in the rear courtyard were decorated with water motifs made of shells, glass and stone. Other embellishment included frescoes, wall paintings and melded cornices.

There can be no finer examples than the Roman mosaics at Pompeii and Herculaneum in Italy which were towns buried in lava, ash and rock after Vesuvius erupted in 79 AD – and were incredibly well-preserved as a result. It is an extraordinary experience to stroll along the streets and drop in at a pub, a bakery, a shop and even a brothel!

Small is beautiful

Micromosaics or ‘mosaico in piccolo’ were developed around 1600 in response to a problem of condensation caused by the very high dome in St Mark’s Basilica at the Vatican in Rome, where altar paintings by famous artists were decaying from dampness.

A desperate search ensued for a lasting material with which to reproduce the paintings. Staff noted that mosaics used in architecture had retained their original condition and colour and began to experiment to find a way of using the medium to copy paintings. Thousands of new shades of tesserae were developed as a consequence, and non-reflective material was found that had the appearance of painting, unlike traditional glass mosaics, which were shiny. By 1770 most of the altar paintings by the great masters had been successfully reproduced in mosaic and to this day most visitors to Saint Peter’s think they are looking at paintings, not mosaics.

Workshops in Rome produced the exceptionally small tesserae from the late 18th century to the end of the 19th century. By 1810 there were 20 micromosaic workshops in Rome. Pieces were often presented as gifts to ambassadors, royal servants and foreign heads of state and were among the gifts given by Pope Pius VII to Napoleon in 1804 on his coronation. They were also snapped up by young men on the Grand Tour.

Coveted technique

Pietre Dure, literally ‘hard stone’, is another form of mosaic, which was developed in Florence during the Renaissance.

It involves the inlaying of precious or semi-precious stones such as agate, amethyst, chalcedony, jasper and lapis lazuli. Pictures were assembled like a jigsaw puzzle to create an almost seamless result. Natural markings in marble and minerals were used to create the effects of light, shade, perspective and pattern.

These difficult techniques were perfected in the Grand Ducal workshops set up in Florence in 1580 and during the 17th century the workshops produced the most magnificent luxury objects made for both ecclesiastical purposes and important people of the day. The medium was used to embellish objects such as snuff boxes and jewellery, furniture and wall panels. It was coveted by many European rulers and was popular with grand English tourists in the 18th century who purchased items for their country houses.

Outstanding collection

The Gilbert Collection of Decorative Arts at Somerset House in London, comprising some 800 objects dating from the 16th to the 19th century, is one of the most important gifts ever made to the country. It contains many superb examples of both micromosaics and pietre dure. It was their outstanding designs and brilliant colours that attracted Sir Arthur Gilbert to collect these mosaics.

In Italia, la moda dei mosaici è cresciuta in Italia dagli inizi del secondo secolo quando un semplice stile bianco e nero è emerso per soddisfare il gusto e la moda degli Antichi Romani.

I mosaici erano un simbolo di stato sociale, che indicava sia la ricchezza che il buon gusto, e tuttavia erano anche usati per abbellire palazzi pubblici come i bagni pubblici (thermae) e negozi. Mosaici a due colori erano considerevolmente più economici da fare, poichè richiedevano tecniche molto più semplici.

Delfini, vita marina, e la mitologia del mare erano immagini diffuse. Anche scene ritraenti la vita degli Antichi Romani quali giochi atletici, la caccia e gli spettacoli del circo erano comuni. Le immagini erano piene di vitalità e impressionanti e più aderenti alla realtà di quelle nella pittura. Mosaici decoravano muri e pavimenti, e nymphaea (are per gli dei) nel cortile retrostante erano decorate con motivi d’acqua fatti di conchiglie, vetro e pietra. Altri abbellimenti includevano affreschi, dipinti a muro e cornicioni fusi.

Non esistono esempi di maggiore finezza dei mosaici degli Antichi Romani di Pompei e di Ercolano in Italia, che furono città sepolte dalla lava, cenere e roccia dopo l’eruzione del Vesuvio del 79 D.C. – e sono stati incredibilmente ben preservati. E’ una esperienza straordinaria passeggiare lungo le strade e infilarsi in un bar, una panetteria, un negozio e persino un bordello!

Piccolo é bello

I micromosaici o ‘mosaico in piccolo’ si svilupparono intorno al 1600 come risposta al problema della condensa causata dall'altissima cupola nella Basilica di San Marco al Vaticano a Roma, dove dipinti dell’altare di famosi artisti venivano rovinati dall’umidità.

Una disperata ricerca portò ad un materiale durevole con il quale riprodurre i dipinti. Gli esperti avevano notato che mosaici impiegati in architettura avevano mantenuto la loro condizione originale e il colore e sperimentarono un modo ed uno strumento per copiare dipinti. Migliaia di nuove serie di tessere vennero sviluppate come conseguenza, e venne trovato materiale non riflettente che aveva l’apparenza della pittura, a differenza dei tradizionali mosaici vetrosi, che erano luccicanti. Intorno al 1770 la maggior parte dei dipinti d’altare dei grandi maestri erano stati riprodotti con successo in mosaici e ai giorni nostri la maggior parte dei visitatori di San Pietro pensa che stia ammirando dipinti, e non mosaici.

I laboratori a Roma producevano le tessere eccezionalmente piccole dal tardo 18mo secolo alla fine del 19mo secolo. Intorno al 1810 c’erano 20 laboratori per micromosaici a Roma. I pezzi erano spesso donati come regali ad ambasciatori, servitori reali e capi di stato stranieri e erano tra i regali dati da Papa Pio VII a Napoleone nel 1804 alla sua incoronazione. Sono stati anche sgraffignati da alcuni ragazzi al Grande Giro.

Tecnica ricercata

Pietre Dure, letteralmente ‘pietra dura’, è un’altra forma di mosaico, che venne sviluppata a Firenze durante il Rinascimento.

Prevede la messa in posa di pietre preziose o semi-preziose come agata, ametista, calcedonia, diaspro e lapislazzuli. I disegni erano assemblati come un gioco delle costruzioni per creare un risultato quasi senza interruzioni. Le naturali venature nel marmo e i minerali erano usati per creare effetti di luce, ombra, prospettiva e motivo.

Queste difficili tecniche vennero perfezionate nei laboratori del Gran Ducato organizzati a Firenze nel 1580 e durante il 17mo secolo i laboratori producevano i più magnifici oggetti di lusso manufatti sia per scopi ecclesiastici che per persone importanti di quel tempo. Il mezzo era usato per abbellire oggetti come tabacchiere e porta gioielli, mobilia e pannelli murali. Era ricercato da molti sovrani europei ed era comune tra i grandi turisti inglesi nel 18mo secolo che acquistavano articoli per le proprie case.

Eminente collezione

La Collezione Gilbert di Arti Decorative nella Somerset House a Londra, comprende circa 800 oggetti datati dal 16mo al 19mo secolo ed è uno dei più importanti regali mai fatti al paese. Contiene molti esempi superbi sia di micromo- saici che di pietre dure. Furono i loro notevoli disegni e colori brillanti che invogliarono Sir Arthur Gilbert a collezionare questi mosaici.