Italy lost its leading artistic role during the 19th century, and artwork from the period remains relatively unknown outside the national confines. But paintings by Macchiaioli, Scapigliati and Divisionist artists are definitely worth seeing. We bring you a guide to the three best museums where you can get an overview of 19th century Italian art.

Giotto’s hieratic Madonnas, the flowing tresses of Botticelli’s Venus, Titian’s sensual Danae, the angst of Jusepe de Ribera’s dark saints, the serene calm of Canaletto’s Venice. The world’s collective imagination is full of Italian art from the Middle Ages to the 18th century—but after that, there’s a hundred years of black hole.

Italy lost its artistic pre-eminence to France in the 19th century so local painters never acquired a reputation outside the national boundaries. Even today names like Giovanni Fattori, Tranquillo Cremona or Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo remain unknown beyond the small circle of art professionals and a handful of international collectors.

Which is a shame because the Italian Ottocento was a time of extraordinary cultural fervour. It saw Italy’s fight against foreign rule, its birth as an independent country, the golden age of opera, and the flourishing of at least three great artistic movements—the Macchiaioli, the Scapigliatura, and Divisionism.

The century opened under the sign of Antonio Canova, the new Phidias, who sculpted beauty out of marble in the graceful, perfectly proportioned style of the ancient classics. He turned Napoleon’s sister, Pauline, into an eternal Venus, while one of his contemporaries, painter Andrea Appiani, captured Napoleon’s Roman nose and rising grandeur in a decidedly imperial portrait.

As the Restoration swept through the peninsula, it sowed the seeds of revolution, inspiring Francesco Hayez’s allegories of Italy bent under the Austrian joke. Works such as the grandiose Profughi di Parga shows the dark sadness of Greek exiles fleeing Turkish rule as a mirror of Italy’s own suffering. In 1861, independence sparked freedom but also social problems, both of which gave birth to new artistic impulses. Many of Tuscany’s Macchiaioli, for example, had taken part in the liberation uprisings and brought the same rebellious spirit to their art. They discarded what they saw as the strictures of the art establishment, choosing instead to depict the world through blotches of colour, and emphasizing the contrast between light and shadow. Giovanni Fattori’s seaside-lounging ladies—undefined patches of white, black and red sheltered under a cream marquee against a vividly azure sea—are emblematic of this style.

In 1861, independence sparked freedom but also social problems, both of which gave birth to new artistic impulses. Many of Tuscany’s Macchiaioli, for example, had taken part in the liberation uprisings and brought the same rebellious spirit to their art. They discarded what they saw as the strictures of the art establishment, choosing instead to depict the world through blotches of colour, and emphasizing the contrast between light and shadow. Giovanni Fattori’s seaside-lounging ladies—undefined patches of white, black and red sheltered under a cream marquee against a vividly azure sea—are emblematic of this style.

Derided at the time—even the name Macchiaioli was a contemptuous take on their blotchy style, as macchia means stain in Italian—these painters are now considered the forerunners of modern art in the country. The same revolutionary approach inspired the Scapigliatura, a literary and artistic movement from the north of the country. Many of the Scapigliati (Italian for dishevelled) had taken part or had supported Garibaldi’s efforts to free Italy, but had then felt betrayed by the newborn Italian government, which they perceived as too conservative. Inspired by the French bohème, they attacked bourgeois values and embraced the intense, anti-conformist, all-consuming life of the poètes maudits, the accursed poets of the French tradition.

The same revolutionary approach inspired the Scapigliatura, a literary and artistic movement from the north of the country. Many of the Scapigliati (Italian for dishevelled) had taken part or had supported Garibaldi’s efforts to free Italy, but had then felt betrayed by the newborn Italian government, which they perceived as too conservative. Inspired by the French bohème, they attacked bourgeois values and embraced the intense, anti-conformist, all-consuming life of the poètes maudits, the accursed poets of the French tradition. Their literature, which has strong anti-clerical, dark, sometimes sexual elements, scandalised the country. Their art privileged light over detail—their contours were soft, the chiaroscuro strong, and they employed tonal colours to convey atmosphere. In Tranquillo Cremona’s The Ivy, for example, two figures are caught in a disturbing embrace—a seated one, dark-haired and clad in black, tries to cling to a standing one, blonde and dressed in white, who would seemingly like to pull back. The strong contrast of colours evokes their different wants, while their shapes merge into a taupe, indistinct background.

Their literature, which has strong anti-clerical, dark, sometimes sexual elements, scandalised the country. Their art privileged light over detail—their contours were soft, the chiaroscuro strong, and they employed tonal colours to convey atmosphere. In Tranquillo Cremona’s The Ivy, for example, two figures are caught in a disturbing embrace—a seated one, dark-haired and clad in black, tries to cling to a standing one, blonde and dressed in white, who would seemingly like to pull back. The strong contrast of colours evokes their different wants, while their shapes merge into a taupe, indistinct background.

The Scapigliati poets, writers and artists, who were the inspiration for Puccini’s opera, La Boheme, influenced the early stages of Divisionism, which is perhaps Italy’s best known Ottocento school. The Divisionists’ vision of art was, in the words of painter Giovanni Segantini, “the investigation of colour in light.” As a result, their technique was to break, or “divide” their paintings into individual brushstrokes of unmixed pigment, which, once seen together, combined into bright, luminous scenes.

The Divisionists’ vision of art was, in the words of painter Giovanni Segantini, “the investigation of colour in light.” As a result, their technique was to break, or “divide” their paintings into individual brushstrokes of unmixed pigment, which, once seen together, combined into bright, luminous scenes.

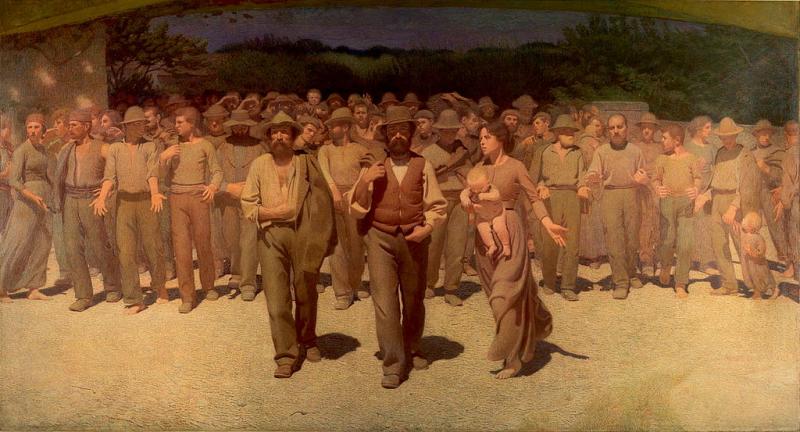

The concept is similar to that of French Pointillism, but Divisionists preferred to employ longer strokes, which sometimes overlapped, rather than restrict themselves to precisely juxtaposed dots. And although they shared the Pointillists’ interest for landscapes, they also branched out into depictions of everyday life that often had political connotations—particularly with Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, whose Quarto Stato (painted in 1901) portrays a strike, with the common people leaving darkness behind them to advance towards light. But 19th century Italy also had some extraordinary painters who, although formed in the country, later embraced the Parisian school. Giovanni Boldini is perhaps the best known among them—a friend of Edgar Degas, he was as influenced by Impressionism as by the Macchiaioli, and developed an elegant, fluid style and interesting use of colour that made him a popular artist. Time magazine called him “a society portraitist as artificial as any who ever stretched a lady’s fingers to tickle her vanity” in a 1933 article, explaining that “he was preeminently the artist of the Edwardian era, of the pompadour, the champagne supper and the ribbon-trimmed chemise.” Indeed, his best works are a celebration of society ladies, black haired flowers wrapped in billowing, cloud-like dresses, but they have such a delicate gracefulness that saves them from being merely an exercise in self-serving flattery.

But 19th century Italy also had some extraordinary painters who, although formed in the country, later embraced the Parisian school. Giovanni Boldini is perhaps the best known among them—a friend of Edgar Degas, he was as influenced by Impressionism as by the Macchiaioli, and developed an elegant, fluid style and interesting use of colour that made him a popular artist. Time magazine called him “a society portraitist as artificial as any who ever stretched a lady’s fingers to tickle her vanity” in a 1933 article, explaining that “he was preeminently the artist of the Edwardian era, of the pompadour, the champagne supper and the ribbon-trimmed chemise.” Indeed, his best works are a celebration of society ladies, black haired flowers wrapped in billowing, cloud-like dresses, but they have such a delicate gracefulness that saves them from being merely an exercise in self-serving flattery.

Giuseppe De Nittis and Federico Zandomeneghi also adopted the French style, the former becoming a society darling, the latter tempering Impressionism with his Macchiaiolo background to capture scenes of bohemian life in Montmartre and celebrate feminine beauty engaged in everyday rituals. But the most fascinating of all the French-influenced artists was perhaps the sculptor Medardo Rosso. A Scapigliato in his youth, he remained a rebel at heart throughout his life—he even called his own son Rebel—rejecting academic constraints and importing Impressionist techniques into sculpture. Obsessed by light, he tried to capture it in wax, bronze and terracotta, manipulating materials to create an illusion of colour. But much like the Scapigliati, the details of his work are not defined—indeed, his sculptures look always unfinished, almost merging with their surroundings.

But the most fascinating of all the French-influenced artists was perhaps the sculptor Medardo Rosso. A Scapigliato in his youth, he remained a rebel at heart throughout his life—he even called his own son Rebel—rejecting academic constraints and importing Impressionist techniques into sculpture. Obsessed by light, he tried to capture it in wax, bronze and terracotta, manipulating materials to create an illusion of colour. But much like the Scapigliati, the details of his work are not defined—indeed, his sculptures look always unfinished, almost merging with their surroundings.

Because the Italian Ottocento is little represented outside Italy, the easiest way to explore its vast, wide-ranging heritage is to visit Italian museums. We have chosen three that showcase 19th century art at its best.

Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Milan

Plagued by a chronic shortage of space, Milan’s Modern Art Gallery is slowly relinquishing its 20th century pieces to other museums to become a genuine collection of Ottocento works. It is fitting because the building itself is a celebration of early 19th century art. Built in NeoClassic style between 1790 and 1796, it was home to Joachim Murat and his wife, Caroline Bonaparte, and later to Eugène Beauharnais and his wife Pricess Augusta Amalia of Bavaria. They commissioned Andrea Appiani to paint a fresco of Mount Parnassus in the villa, which is one of the museum’s highlights.

Plagued by a chronic shortage of space, Milan’s Modern Art Gallery is slowly relinquishing its 20th century pieces to other museums to become a genuine collection of Ottocento works. It is fitting because the building itself is a celebration of early 19th century art. Built in NeoClassic style between 1790 and 1796, it was home to Joachim Murat and his wife, Caroline Bonaparte, and later to Eugène Beauharnais and his wife Pricess Augusta Amalia of Bavaria. They commissioned Andrea Appiani to paint a fresco of Mount Parnassus in the villa, which is one of the museum’s highlights.

The permanent collection, however, matches these exalted surroundings. The ground floor is home to NeoClassic works from the late 18th and early 19th century, with Appiani’s paintings and statues by Canova and Pompeo Marchesi, and the first Romantic pieces, with early paintings by Hayez and Massimo d’Azeglio’s dark, gloomy La Vendetta.

The second floor is a cavalcade through the rest of the century, with a good selection of Hayez’s work, the grand, official paintings of the independence years, Piccio’s intense portraits, the strong visual contrasts of the Scapigliati movement, the exquisite elegance of Boldini, De Nittis and Zandomeneghi’s pieces and what is perhaps Italy’s best collection of Divisionist art, including Segantini’s Le Due Madri.

The tour ends, visually, as well as chronologically, with Pellizza da Volpedo’s revolutionary Quarto Stato. But wait! There is more on the second floor, which houses the Raccolta Grassi, a collection of international works from the Middle Ages to the 20th century, with a particularly good selection of Macchiaioli and some interesting pieces by Zandomeneghi, De Nittis and Boldini.

Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Villa Reale, Via Palestro 16, Milan. Open Tuesday to Sunday 9am to 1pm and 2pm to 5.30pm. Free admission (http://www.gam-milano.com/).

Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Roma

The origins of Rome’s modern and contemporary art museum hark back to the days when Fattori, Segantini and Boldini were painting their masterpieces, some of which, like Fattori’s La Battaglia di Custoza, were acquired at the time. Founded in 1883, the Gallery initially concentrated on verist, simbolist and decadent art. Later, it expanded its selection with more pieces by the Macchiaioli, the Divisionists and Medardo Rosso.

The origins of Rome’s modern and contemporary art museum hark back to the days when Fattori, Segantini and Boldini were painting their masterpieces, some of which, like Fattori’s La Battaglia di Custoza, were acquired at the time. Founded in 1883, the Gallery initially concentrated on verist, simbolist and decadent art. Later, it expanded its selection with more pieces by the Macchiaioli, the Divisionists and Medardo Rosso.

Today, the 19th century rooms house NeoClassic works by the likes of Appiani and Canova, and grand Romantic paintings—including Hayez’s Vespri Siciliani, a celebration of the Sicilian rebellion against Angevin rule which took place in the Middle Ages—followed by the everyday scenes of the Macchiaioli, the intense chiaroscuro of the Scapigliati and De Nittis’ elegant society vignettes.

But perhaps the most interesting pieces are those by Southern Italian painters, whose work is hard to find elsewhere in the country. The gallery has a large collection of paintings by Filippo Palizzi, an Abruzzo artist with a penchant for depicting farmers, animals and shepherds, Domenico Morelli, who excelled in the historic genre, and Gaetano Previati, who brought divisionism techniques into the 20th century.

Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, Viale delle Belle Arti 131, Rome. Open Tuesday to Sunday 8.30am to 7.30pm. Admissions €10, concessions €8 (www.gnam.arti.beniculturali.it).

Galleria Civica d’Arte Moderna e Contemporanea (GAM), Turin

The squat, late-1950s building that houses Turin’s modern and contemporary art collections belies the museum’s ancient origins. GAM was founded in 1863 as Italy’s very first civic gallery devoted to modern art.

The squat, late-1950s building that houses Turin’s modern and contemporary art collections belies the museum’s ancient origins. GAM was founded in 1863 as Italy’s very first civic gallery devoted to modern art.

A troubled history saw it move several times, then close for many years to allow a complete restoration. But now the museum has one of the most extensive collections of Northern Italian Ottocento art, with some interesting examples from further afield.

The tour opens with Canova’s Sappho and some early 19th century paintings from Piedmont, but NeoClassicism soon gives way to the strong emotions of Romanticism, with Hayez’s melancholic Carolina Zucchi and Massimo d’Azeglio’s historic landscapes.

The gallery’s highlights, however, are Antonio Fontanesi’s exquisite landscapes, caught between the attempt to depict nature and the knowledge that you can only capture fragments of it—the light playing on water in Bagliori sulla Palude is in itself worth a visit.

GAM also has some interesting paintings by the Scapigliati (including Cremona’s The Ivy) and the Macchiaioli, as well as Boldini’s lovely Portrait of a Lady.

GAM, via Magenta 31, Turin. Open Tuesday to Sunday, 10am to 6pm. Admissions €7.50, concessions €6 (www.gamtorino.it).