Coffee’s greatest appreciators are something of a fraud when you take a glance at the history books. Italy has never produced its own coffee. It never even ruled a major coffee-growing colony, as horrible as that sounds.

And yet, the country is so synonymous with coffee that Italophiles dream of visiting Restoration-style bars and sipping from impossibly tiny cups with elegantly dressed locals. Tourists still tell me stories of friends of friends who ordered a latte in Rome and were given a glass of milk. And others who were flatly refused a cappuccino after 10am.

In reality, Italy is as susceptible to globalisation as the next country. Just ask all the Milanese who can’t wait for the first Starbucks to open. There is no true Italian espresso. Like anything else, it is ruled by the sway of time.

The first espresso

At the turn of the century, Italian inventor Luigi Bezzerra was the first to produce a single shot espresso in a matter of seconds. His caffé espresso pushed water and steam through a puck of coffee directly into your cup, splashing a significant amount of scalding water onto the barista in the meantime. Unsurprisingly, the machine didn’t catch on. That is until Bezzerra met Desiderio Pavoni, who made a few adjustments and revealed the new and improved model at the 1906 Milan fair. The pair called it Ideale and it dominated Italian market for decades.

But Italians were never going to be happy sipping espresso at their favourite bar. Espresso shouldn’t have opening hours. It should be enjoyed 24/7 without having to put on a jacket and shoes. Enter Alfonso Bialetti. The first stove-pot coffee maker or Moka was released in 1933. For the next six years, the humble little contraption would be sold at weekly markets in Piedmont. It wasn’t until after WWII that the Moka invaded Italian households.

Out of the bar and onto the stove

Unlike its predecessor, the Moka was a low-pressure extraction machine, which made a stronger espresso with a different flavour profile and no crema.

For most Italians, Moka remains a source of nostalgia. I remember pulling ours out at family parties well into the ‘90s. It was a fail safe when you had visitors and wanted to make a lot of coffees quickly. Every time we used it, the smell of toasted beans would fill our kitchen and everyone would watch the steel volcano with anticipation. Look away for a second and coffee would spray everywhere.

As the Moka faded into the background, most Italians ignored the American percolators and filter coffees and tried their hand once more at a traditional espresso machine.

Space age gadgets

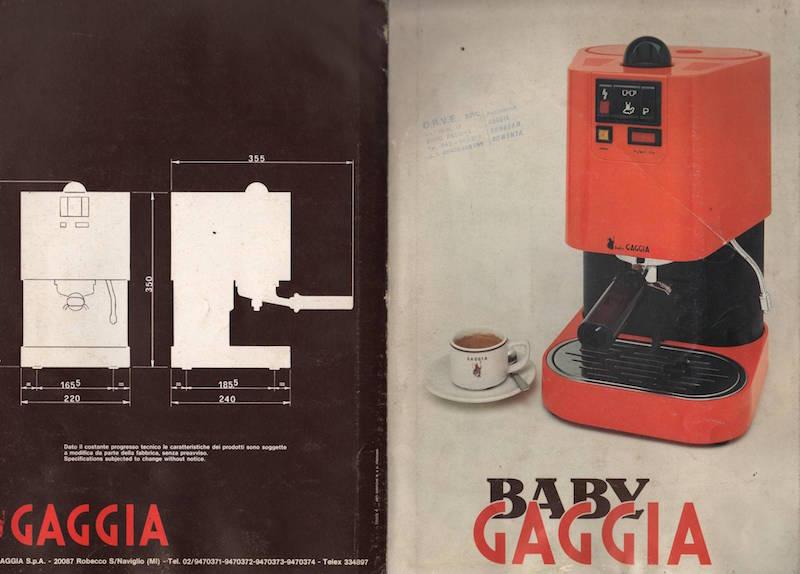

The first espresso machine designed for the home was released in 1948. As the story goes, patrons weren’t impressed. They asked Achille Gaggia what the “schiuma” or scum was on the top of their espresso. Ever the industrious Italian, Gaggia turned this flaw into a marketing ploy, renaming his drink “caffé crema” and coining the phrase that espresso aficionados continue to use in the most insufferable manner.

The Gaggia Gilda cost 35,000 lire, about 16 euro. Its selling point was that you could enjoy bar coffee at home, something that every domestic espresso machine has promised since. From Faema to Bosch to Miele, almost every household appliance company has tried their hand at making this Italian icon.

In my kitchen, our espresso machines were marked by their inventible failure. They made a more satisfying espresso than the Moka. The crema was better and the taste more complex. But more often than not the huge hulking beasts of steal and chrome would burn every bean because we couldn’t figure out how to set the temperature and the flimsy bargain buys made coffees that were two-thirds soggy grains, one-third liquid.

They all had one thing in common though. They were beautiful alienesque machines that promised espresso bliss if only we could master the art of being a barista. It was in this age of confusion that Eric Favre, a Swiss engineer working at Nestlè produced the first single-serve coffee container in 1976.

The rise of the pod

Nespresso wouldn’t patent their process for brewing espresso from capsules until 1997. By then, Lavazza had cottoned on and the pod domination began.

A lot of people think Italians shun coffee pods as an affront to the purity of the espresso. A Nielson study published in La Repubblica in 2014 estimated 2.6 million Italian households, about 11 per cent, use coffee capsules, a number that has doubled since 2011.

In Italy, pod users, like myself, still want the same thing they wanted in 1948, a coffee that’s as good as the one you get in a bar. For most Italians, coffee remains a ritual. It’s not about convenience. Pod machines are easier to use than a traditional espresso machines and more reliable.

Of course there are still those who don their hat and cane and head to the bar each morning, just as there are those who swear by their Moka or their cranky old Gaggia. But as tastes change, the modern Italian coffee scene is in flux. Perhaps the next espresso you’ll enjoy in that Roman restoration bar will be a cold brew served on tap?