This weekend marked 461 years since Galileo Galilei came into the world and began building a legacy that would inspire countless curious people to reach for the stars. One of his current-day “heirs” is Fernando Pedichini, originally from Orvieto in Umbria.

Dr. Pedichini is a renowned astrophysicist, astronomer and researcher who co-discovered his first asteroid in 1996. Today he works in Rome for the National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) where he is the coordinator of the SHARK-VIS project, whose namesake instrument uses what’s known as a “fast imaging” approach to remove the earthly atmospheric turbulence that can distort images from outer space — resulting in high-quality, unprecedentedly precise renderings of exoplanetary systems.

We chatted with Dr. Pedichini recently about his team’s achievements and about Italy’s place in the “deep space” race.

This interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

Dr. Fernando Pedichini on Italy’s spot in the space race

Italy Magazine: What was it like to be the main architect of the SHARK-VIS project that captured high-res celestial images in space?

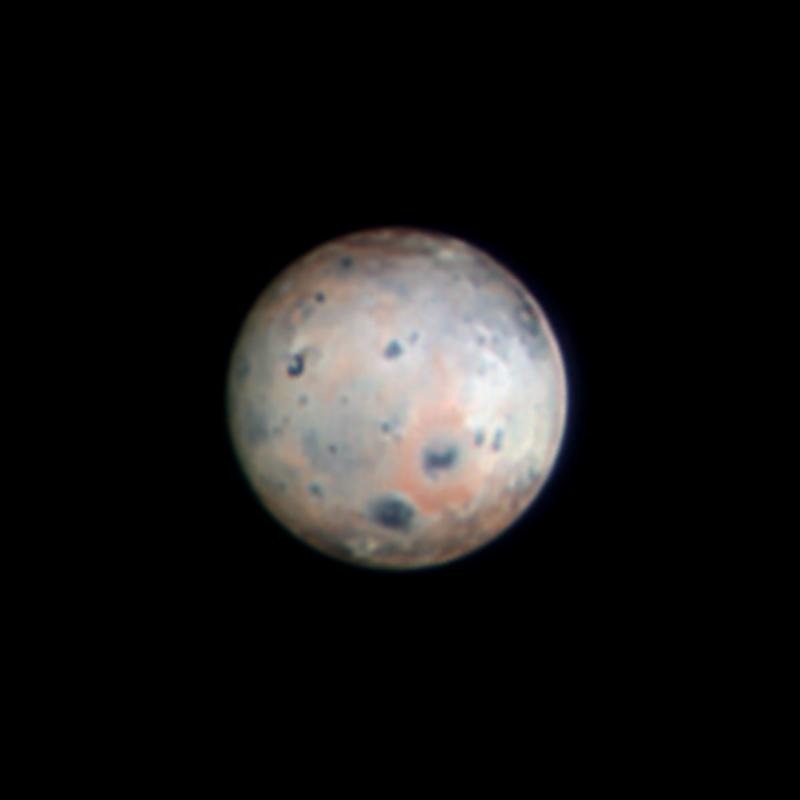

Fernando Pedichini: It wasn’t only from space, but also to space from the ground! After Galileo’s discoveries and use of telescopes, these optics became mainstream. Italian companies have been building some of the largest telescopes in the world, such as the upcoming ELT (Extremely Large Telescope), the ESO’s VLT, and the Large Binocular Telescope (LBT) [ed. which Pedichini and his team used in 2024 to capture images of Io, one of Jupiter’s “Galilean moons,” in the highest resolution ever obtained with an Earth-based telescope].

This [project] revealed details that are not common from ground observation. They compare to the ones you can only get with very expensive images from space probes, which are not always available because of orbital dynamics and mission plans, so we opened what I’ll call a “low cost” (only at $10,000 per hour!) alternative to planetary scientific observation.

IM: We know that Italy was one of the earliest countries in the world to achieve a successful satellite launch program, sending San Marco 1 into orbit in 1964 — just seven years after the Soviets’ Sputnik. Can you tell us about the most recent strides Italy has made that have significantly contributed to the modern space race?

FP: Most of the housing of the International Space Station (ISS) is made in Italy. Yes. This small country is one of the top providers for the building and maintenance of the still operational and largest space experiment ever built by mankind.

ALTEC (Aerospace Logistics Technology) in Turin is responsible for the control and communication of the ISS, the Telespazio large dish antennas, together with the Malindi station (and soon the INAF Sardinia Radio Telescope) — all part of the deep space network. The Sardinian telescope is one of the most powerful data links used by NASA, ESA, JAXA, and so forth to communicate with deep space robotic missions, such as the Juno spacecraft or the Voyager — the farthest-reaching object mankind has ever sent into space.

ASI (The Italian Space Agency) has a series of proprietary rockets (whose main components are built and assembled near Rome) and the VEGAs, which are capable of carrying low and high orbit unmanned payloads.

There are a lot of small and medium-sized industries spread all over Italy that provide components for a lot of space projects, from CubSat (a class of small satellite) components to rocket engines! Yes, in Italy the space economy is growing fast.

IM: What does all this exciting work mean for the future of Italian space exploration?

FP: Space is an unlimited playground where we can run with projects and thoughts. In this framework we are working together with engineers to reach ambitious goals such as exoplanet exploration with ground and space-based telescopes, which are becoming larger and more sensitive.

We have a plan to set up the three-meter-wide ELT in the Atacama Desert in Chile and the Habitable World Observatory project in the deep space. This 12-meter space telescope will be dedicated to the discovery and characterization of habitable exoplanets, investigating their evolution with hopes of finding exobiological forms of life. This will help mankind better understand what’s in store for the future of our blue planet and how to keep it safe.

Inspired by Dr. Pedichini’s path? Here are four “interstellar” Italians you should know.

Amalia Ercoli Finzi

The first woman in Italy to graduate with a degree in aeronautical engineering (1962), 87-year-old Amalia Ercoli Finzi went on to become a leading figure in the field of aerospace science and technology. She was a consultant for NASA, ASI, and ESA, and was a principal investigator for the SD2 instrument on the Rosetta space probe.

Roberto Ragazzoni

Named president of the National Institute of Astrophysics (INAF) in April 2024, Roberto Ragazzoni’s contributions to the field of space exploration are mostly in the development of the large telescopes that today allow progress in astronomical knowledge.

Barbara Negri

Barbara Negri is the head of the Human Flight and Science Experimentation Unit at the Italian Space Agency (ASI). Among her many duties, she conducts scientific exploration of the moon and Mars. Her work addresses the need for humans to investigate “to infinity and beyond.”

Samantha Cristoforetti

Christened “AstroSamantha” by her many admirers, Samantha Cristoforetti is the first European woman to command the International Space Station (ISS), and was also the first Italian woman in space. In 2015, the Milan-born astronaut was awarded the Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic — one of Italy’s highest honors.