The French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson once observed that “photography is easy; painting is difficult.” What’s nearer to the truth is that Cartier-Bresson made photography look easy. He was, in fact, continually on the run, snapping away in the quest for that elusive spontaneous shot. Cartier-Bresson had an eye for the perfect summing up of a mood, a state of mind, even a moment in history, so that whatever he chose to shoot would forever capture a little piece of life — perhaps poignant, perhaps amusing, but always memorable, always humane.

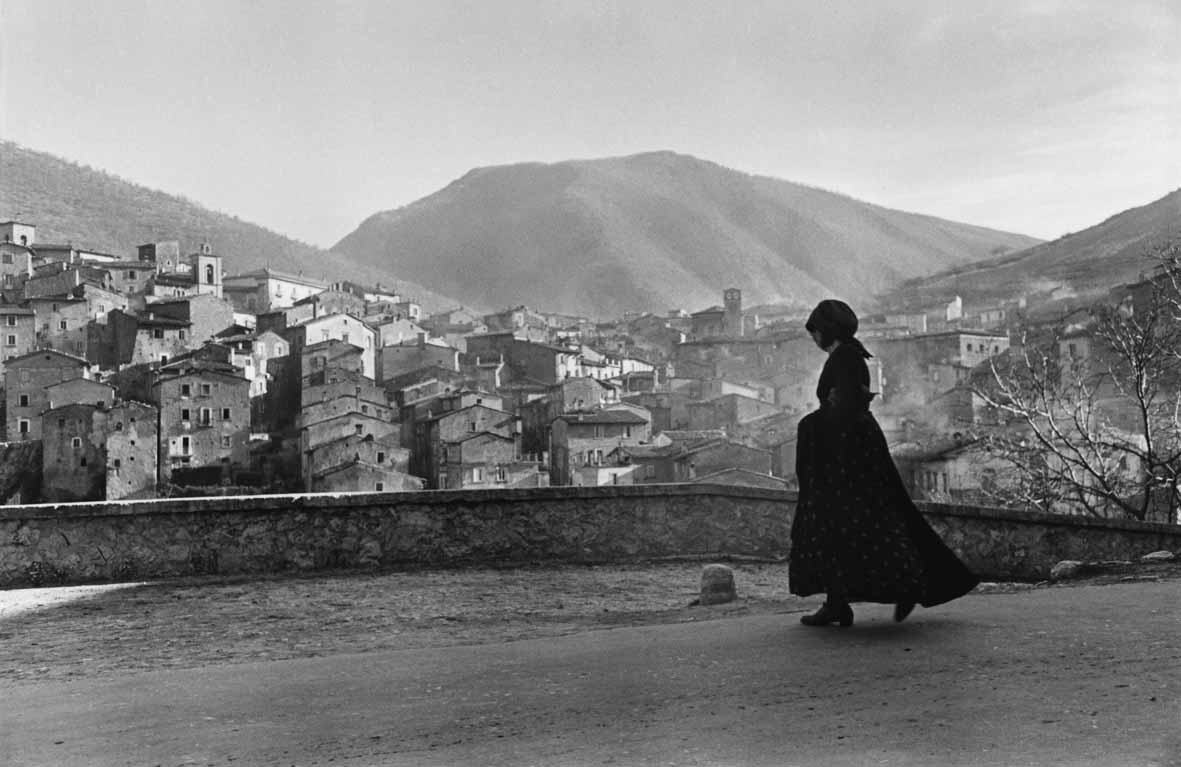

Cartier-Bresson first visited Italy in the 1930s, but the most famous of his black and white images of Italy came after World War II; he was particularly adept at capturing the south and its socioeconomic struggles, and did so until abandoning photography altogether in the 1970s. Featured in popular magazines, including Holiday and Harper’s Bazaar, Cartier-Bresson’s photographs helped bring the “Mezzogiorno” to international attention and provide the basis for a push toward modernization. He didn’t have to champion any particular political agenda; the images spoke for themselves.

Now, 20 years on since Cartier-Bresson’s death, many of these images are on display in Rovigo, Veneto, at the superb exhibition Henri Cartier-Bresson e l’Italia at Palazzo Roverella, which offers incredible insight into 1930s-1970s Italy and shows just how much the country has changed — and, in some cases, quietly stayed the same.

Before abandoning his photography career in the 1970s, Cartier-Bresson captured both the hardships and humor of everyday life, in the streets and piazzas, showcasing people who were perhaps downtrodden, but who rarely seemed to be in despair. Many of these photos recall, in both aesthetic and mood, the neorealist movement in Italian films of the 1940s and early 1950s. There are shots of the tattered clothes, the miserable offerings on market stalls; but there are also people shown gossiping in the streets, snatching moments of cheerfulness amid the deprivation.

Cartier-Bresson seems to have particularly enjoyed photographing the freedom and exuberance of children at play, perhaps because of their uninhibited absorption in their games, as is demonstrated in so many of his images, like the headlining photograph of playtime on Piazza del Campo in Siena (above). But he also expertly captured moments of tranquility; one amusing photograph in the show features a whole nursery class having an afternoon nap.

Cartier-Bresson’s lens on life in the Italian south

Much of Cartier-Bresson’s time in Italy was spent in the south, particularly Basilicata, where he first traveled for a 1951 commission on behalf of the Italian authorities. He developed a fondness for Matera, returning there in the 1970s, and his photographs from the period bore witness to the enormous changes that the country underwent in the second half of the 20th century. The final portion of the exhibition focuses on these images and the tension between vestiges of the past and the intrusion of industrialization; this was, as the exhibition organizers remind, the age of Olivetti and Alfa Romeo.

Cartier-Bresson’s interest in this clash helped him to develop a kinship with writer and intellectual Rocco Mazzarone, who explored similar themes of the “southern question” in his work. But Cartier-Bresson was not just academically interested in Basilicata, but emotionally engaged with it; in 1976, he wrote to Mazzarone professing attachment “to the country and the people we have met.”

Cartier-Bresson’s images even beyond Basilicata reflect this sensitivity: They can be surprising, poignant and even disturbing, but are always sympathetic.

Go see the Palazzo Roverella exhibition if you can, but if Rovigo is too remote, look up the work of this man in the Magnum archives. You’ll uncover the upheavals of 20th-century Italy through the lens of a thoughtful observer, who documented the changes with a sometimes critical but always affectionate eye.

If you go

Henri Cartier-Bresson e l’Italia

Ongoing until January 26, 2025

Palazzo Roverella, Rovigo

Tel. +39 0425 460093

Website