Dinner in antiquity was almost always a social affair shared with a few close friends at someone’s home.

The ancient Romans thought that the ideal number of guests for a dinner party were between three, for the number of Graces,to nine, for the number of Muses. The ideal number of guests was cause for much debate in antiquity. Some hosts speculated that small numbers of guests were preferable to avoid the embarrassment of running out space or wine and food. Others, such as Plutarch, Greek-born writer who later became a Roman citizen, wrote, “If both space and the provisions are ample, we must still avoid great numbers, because they in themselves interfere with sociability and conversation.”

INVITATIONS

For informal dinner parties the ancient Roman host extended a verbal invitation, usually during a workout at the public baths. For larger or more formal events, messengers delivered hand-written invitations to guests. Several, written on papyrus, were discovered at the Alexandria library in Egypt. One wedding invitation from the third century AD reads, “Theon son of Origenes invites you to the wedding of his sister tomorrow, Tubi 9, at the 8th hour.” My favorite, also from the third century, states, “Greeting, my lady Serenia, from Petosiris. Make every effort, dear lady, to come out on the 20th, the birthday festival of the god, and let me know whether you are coming by boat or by donkey, in order that we may send for you. Take care not to forget, dear lady. I pray for your lasting health.

SEATING

In antiquity the place of honor varied from city to city. For some it was the head of the table and for others the central section. Plutarch, explianed that the seat of honor is for “the Persians the most central place, occupied by the king; the Greeks the first place; the Romans the last place on the middle couch.”

Do you sometimes wonder whether or not to set out place cards for your dinner party? Well, you are not alone; the ancients debated the issue too. Ancient Romans like Plutarch discussed the philosophical merits of “whether the host should arrange the placing of his guests or leave it to the guests themselves.” Then, just as now, both assigning seats, and not, had merit. Some ancients argued that seats should be assigned to give due respect to a guest’s age and rank. They considered it rude not to assign persons of special status a place of honor or not seat him near other important guests.

Others, also in favor of assigning seats, felt the decision should be based on who will get along rather than on rank. “For it is not prestige, but pleasure which must determine the placing of guests; it is not the rank of each which must be considered, but the affinity and suitability of each to each.” Still others argued that the guests should decide for themselves where and with whom they are most comfortable sitting. Plutarch’s advice was to “separate contentious, abusive and quick-tempered men by placing between them some easy-going men as a cushion to soften their clashing” and match guests whose personality style and interests complement one another.

DINING

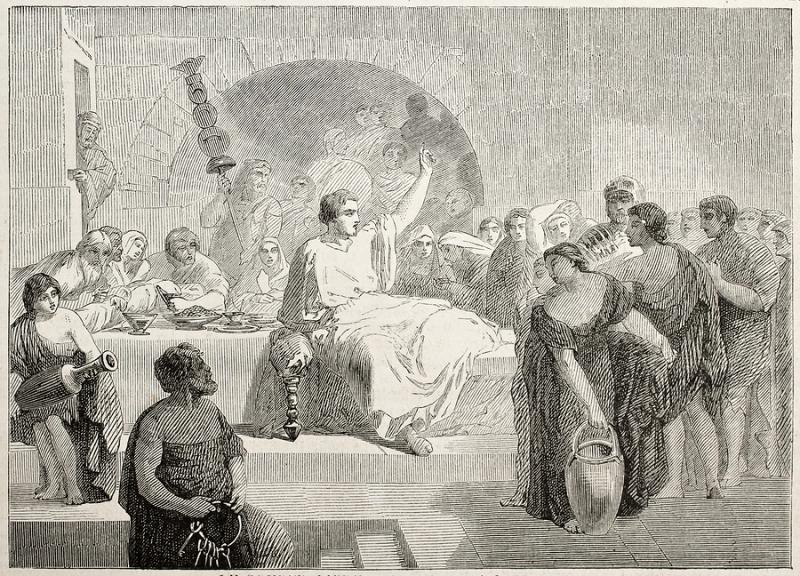

The ancient Romans ate reclining on couches in dining rooms lavishly decorated with frescos, mosaics, wall hangings and art objects. To add to the festive mood they scattered flower petals on the floor before a feast. Some flowers were thought to protect guests from food poisoning. The ancient Romans were very superstitious. They believed that any food that fell on the floor during a meal belonged to the gods and it was considered bad luck to sweep it up during dinner. The ancients Romans even decorated their dining room floors with mosaics depicting realistic-looking scraps of fallen food. Our modern-day custom of throwing a pinch of salt over your should for good luck came from ancient times. Back then, if salt spilled on the table the ancients would toss a bit more onto the floor as an extra gift to the gods to ward off angering them and avoiding reprisals.

The Romans, like the Greeks before them, did not use forks but ate elegantly with their fingers, following such etiquette nuances as picking up preserved fish with one finger but fresh fish with two.

CONVERSATION

I love reading about ancient dinner conversations. Plutarch mentions dinner conversations ranging from such far-flung topics as “whether the hen or the egg came first” and “whether the sea is richer in delicacies than the land.” Another topic weighed the health merits of eating a wide variety of foods. For Plutarch: “variety is more agreeable, and that the more agreeable is the more appetizing, and the more appetizing is the more healthful.”

Marcus Varro, the ancient Roman writer and scholar, suggested rules for the right mix of guests for dinner parties, “Do not invite either too talkative or too silent guests, since eloquence is appropriate to the courts, and silence to the bedroom, but neither to a dinner.”

The social exchanges that occur over food and wine were as important to the ancient Romans as to us today. Important in creating and maintaining friendships and important in gaining an understanding of others through the exchange of ideas. Plutarch observed, “A guest comes to share not only meat, wine, and dessert, but conversation, fun, and the amiability that leads to friendship.” Plutarch goes on to add, what all of us who have spent any time lingering over wine with friends intuitively know, “drinking together does give men a chance to get some understanding of each other.”

Like modern Italians, the ancient Romans appreciated good conversationalists and enjoying hours at the table chatting with friends. The ancient Romans even offered advice on how to improve conversation skills. Philosophers of the time suggested that hosts should ask questions on a topic someone knows well to spark interesting conversation, “Thus travelers and sailors are very glad to be questioned about a far-away place and a foreign sea and about the customs and laws of alien men.”

Like this article? Don't miss "In Rome, Nero’s Domus Aurea Comes to Life with 3D Animations."

JOKES

Marcus Martial, who lived during the reign of Nero, wrote hundreds of short humorous poems called epigrams, which provide one of my favorite glimpses into the past. Martial unabashedly admits to sending honey cakes to elderly men in the hopes of a mention in their wills and of finagling invitations to choice dinner parties. His poems touch on many aspects of daily life including men’s talk at the public baths, Roman women’s supposed promiscuity, gladiators sold at auction, snail forks, and the virtues of coming to a dinner party with your own napkin.

Plutarch, the first century historian, tells my all time favorite tall-tale. I can just imaging Plutarch regaling dinner guests with the story of how supposedly Mark Anthony wanted to impress his mistress Cleopatra with his fishing prowess, so secretly positioned swimmers under their barge to attach fish to his line. At some point the slaves ran out of fresh fish and attached dead salt fish to the line. Cleopatra, who realized what he was doing all along, tactfully reassured Mark Anthony to leave fishing to others. “Your game”, she said “is cities, provinces, and kingdoms.”

Marcus Varro, an ancient Roman author, wrote a book of humorous essays and advised that conversation at dinner parties should be “diverting and cheerful” and that guests should remember to “talk about matters which relate to the common experience of life.” Jokes and story telling were then, just as now, a lively part of dinner conversation in Italy and certain guests were invited to dinner because of their wit. Two thousand years ago, Plutarch counseled that “the man who cannot engage in joking at a suitable time, discreetly and skillfully, must avoid jokes altogether” and that humor should be “casual and spontaneous, not brought in form a distance like previously prepared entertainment. ” Still sounds like good advice today.

Martial’s books of epigrams were often given to dinner guests as a parting gift. Here are three of Martial’s deliciously witty poems:

-1-

Although you’re glad to be asked out,

whenever you go, you bitch and shout

and bluster. You must stop being rude:

You can’t enjoy free speech AND food.

-2-

Three hundred guests, not one of whom I know-

And you, as host, wonder that I won’t go.

Don’t quarrel with me, I’m not being rude:

I can’t enjoy sociable solitude.

-3-

Readers and listeners like my books,

Yet a certain poet calls them crude.

What do I care? I serve up food

To please my guests, not fellow cooks.

FOOD

Many delicacies found on a table in antiquity are served today. Dishes such as pesto, custard, pasta, pizza, and pancakes all have their roots in ancient Rome. The recipes below all come from my book The Philosopher’s Kitchen: Recipes for Ancient Greece and Rome for the Modern Cook (Random House)

Egg dishes, like the Asparagus Frittata below, were popular appetizers in antiquity as we can infer from the Latin saying, ab ovo usque ad malum, “from egg to fruit,” the equivalent of our expression, soup to nuts.

The frittata pairs well with the Mint Marmalade, which is one of more than 100 sauce recipes for grilled meats listed by the Roman gourmet Apicius. In antiquity ingredients were ground in a mortar to use raw or to incorporate into sauces. Apicius uses this grinding method so often that he is referred to as the “mortar chef.”

-1-

Asparagus Frittata

Serves 4

This delicious asparagus frittata makes a perfect appetizer or, served with salad, an elegant light lunch.

6 large eggs

1/2 teaspoon ground coriander seed

1/2 teaspoon dried savory

2 tablespoons minced fresh parsley

Salt and freshly milled pepper

3 tablespoons olive oil

12 thin asparagus stalks, cut into 1-inch pieces

1 small purple onion, minced

3 tablespoons crumbled feta cheese

2 tablespoons minced fresh chives

Beat the eggs, coriander, savory, and parsley in a bowl. Season to taste with salt and pepper. Set aside.

Heat the oil in a skillet over high heat. Add the asparagus and sauté until tender, about 4 minutes. Add the onion and continue cooking on high until golden, 3 to 4 minutes.

Lower the heat to medium, pour in the egg mixture, and scramble slightly to mix. Cook until just set and beginning to turn golden. Invert the frittata onto a greased flat plate and then slide the frittata back into the pan to cook the other side until golden.

Top the frittata with feta and chives, cut into quarters, and serve warm.

-2-

Mint Marmalade for Grilled Meats

Serves 8

The marmalade is delicious with any grilled meat, but especially lamb. It’s also wonderful on grilled vegetables, fish, or chicken.

1/4 cup raspberry or other fruit vinegar

2 tablespoons golden raisins

4 dates, minced

1 teaspoon honey

2 tablespoons pine nuts

2 tablespoons grated Grana Padano cheese

1 cup fresh mint leaves

3 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

Salt and freshly milled pepper

Simmer the vinegar, raisins, dates, and honey in a small sauce pan over medium heat until the raisins are soft, 2 to 3 minutes. Allow to cool to room temperature.

Puree this mixture, along with the pine nuts and cheese, in a food processor until smooth. Add the mint leaves and pulse until minced. Slowly add the oil and continue blending until smooth.

Season to taste with salt and pepper.

-3-

Braised Chicken with Peaches and Squash

Serves 4

Squash was one of the most popular and frequently served vegetables in ancient Roman time.

4 chicken legs and thighs, separated

Salt and freshly milled black pepper

All-purpose flour for dredging

2 tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

1 teaspoon caraway seeds

1 1/2 teaspoons ground cumin

1 acorn squash, peel on, sliced 1/2 inch thick

2 cups dry white wine

1 firm peach, skin on, thinly sliced

2 tablespoons minced fresh cilantro

2 tablespoons minced watercress

Liberally season the chicken with salt and pepper, and dredge in flour. In large sauté pan, warm the oil over high heat and brown the chicken on all sides. Remove the chicken from the pan. Remove all but 3 tablespoons of the remaining pan juices and add the caraway, cumin, and squash. Cook the squash until golden, 2 to 3 minutes.

Add the wine to the squash slices and bring to a boil. Return the chicken to the pan, cover with a tight lid, and reduce to low heat. Simmer, stirring occasionally, for 30 minutes, or until the chicken is cooked through.

Remove the chicken and squash from the pan and arrange on a serving platter. Add the peaches to the pan juices and simmer for 5 to 10 minutes, or until the liquid is reduced by half. Remove from heat. Stir in the cilantro and watercress, and then pour over the chicken and squash.