Outgoing health minister Livia Turco on Wednesday lifted the ban on embryo screening in assisted fertility procedures in a last-minute update to national guidelines before the new centre-right government takes power.

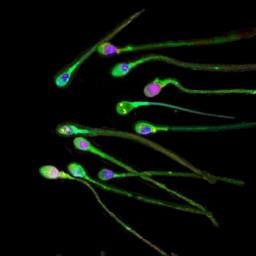

Under the new guidelines, couples in which the male partner has a sexually transmitted disease such as HIV and hepatitis B and C - and which are therefore considered 'sterile' in that they cannot reproduce without putting the mother or baby at risk of infection - will also be able to take part in in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) programmes.

Turco described the new guidelines as ''the fruit of extensive work'' and explained that they were necessary after several high-profile court cases that overruled sections of the original, controversial law passed in 2004, known as the 'legge 40', which imposes tight restrictions on assisted fertility techniques.

Pushed through parliament by an alliance of Catholic law-makers on the left and right, the law forbade the screening of embryos for abnormalities or genetic disorders, even for couples with a history of genetic disease.

Women were also denied the right to refuse implantation once their eggs have been fertilised, following the Catholic church's position that embryos are fully-fledged human beings and cannot be discarded on the basis of alleged 'defects'.

But in January, the Lazio regional administrative court, or TAR, ruled that a ban on the screening of embryos to be implanted in a woman's uterus went beyond the rightful powers of the legislator.

The decision followed on the heels of another case in September, when a Sardinian court upheld a mother's request that doctors screen her in-vitro embryos for a hereditary blood disorder.

The woman, who was herself a carrier of the disease, only wanted the embryos implanted if she knew there was no chance they would develop the disorder.

Turco said on Wednesday that the new guidelines would provide health workers with ''suitable and punctual instructions'' in the light of the court rulings.

The new guidelines were welcomed as a step in the right direction by assisted fertility campaigners who want to see many of the restrictions lifted from the law.

''They're positive, but still incomplete,'' said Filomena Gallo, president of the Amica Cicogna infertility association.

''Carriers of genetic diseases who are not sterile are not catered for in the text and are not able to undergo assisted fertility. They are not permitted the same concessions as the carriers of viral diseases,'' she explained.

Well-known fertility specialist Severino Antinori, who shot to fame in 1994 when he helped a 63-year-old woman give birth, said the guidelines did not go far enough to resolve ''anti-constitutional'' violations regarding health and research.

''We have to hope that the new parliament will respect these amendments and also improve the law further,'' he said.

But some Catholic politicians reacted with outrage to what they saw as Turco trying to slip through controversial amendments when both she and the last government had already been ''sacked''.

The family representative of the centrist Catholic UDC party, Luisa Capitanio Santolini, described the amendment as ''a poisoned arrow that has the flavour of a vendetta''.

Calls came from both the UDC and premier-in-waiting Silvio Berlusconi's People of Freedom Party for the new minister of health - who has yet to be appointed - to retract the guidelines.

RESTRICTIVE LAW.

Italy's assisted fertility law is one of the most restrictive in Europe.

Under the law, singles, same-sex couples and women beyond child-bearing age are banned from using assisted fertility techniques, which are limited - and only as a last resort - to sterile heterosexual couples who are married or live together on a ''stable'' basis.

A maximum of three eggs are allowed to be fertilised at one go and they must all be transferred to the womb simultaneously.

The use of donor sperm or eggs, surrogate mothers and embryo freezing or experimentation are also banned.

Experts say this lowers the chances of conception compared with the past practice of freezing embryos for future implant attempts.

In July last year, Turco blamed the 2004 law for an almost 4% decline in the number of babies conceived using in-vitro fertilisation (IVF) in Italy between 2003 and 2005.

Supporters say the law respects the rights of the human embryo, preserves the family as the fundamental social unit and ends decades of unregulated practices.

But critics accuse Catholic politicians of bowing to the Church with highly restrictive norms that allegedly place women's health at risk and deny sterile couples many of the options that are standard treatment in other European states.

The number of Italian couples going abroad for the fertility treatment quadrupled to almost 4,000 between 2004 and 2006 in efforts to bypass the law.